The 1970s are right back in fashion all over again, dear blog reader. You might have noticed this. In fact, it's been somewhat hard to miss of late. Various nostalgia-based continuations, or 'reimagings' of some long-cancelled TV dramas (Doctor Who, Survivors), the revivals of a bunch of old telly formats like Superstars and The Krypton Factor and the popularity of quasi-historical drama series set during the era - Life on Mars most obviously - have conspired to, suddenly, give the era a polished novelty kitsch value which, to be honest, nobody really noticed about it at the time. At least, not if they were walking around with their eyes open, that is. Proof, if any were ever needed that it's difficult, but not impossible, to polish a turd.  '1984 was just like 1974,' the songwriter and social commentator Jerry Dammers once noted. 'A miners strike and a load of crap in the charts.' This oddest of nostalgia trips has been building for quite a while and, to be honest, it rather baffles this blogger. It's a little bit like the annoyingly cosy nostalgia that many of my parents generation had (and, indeed, still have) for the 1930s and the 1940s. Why would anybody want to remember fondly an era of warfare and carnage, depression, deprivation, rationing and rickets? It's the same with the 1970s, frankly. Why would anyone in their right mind wish to celebrate The Era That Taste Forgot? 'In the Seventies there was long hair/there were left-over hippies everywhere/and I should know cos I was there,' wrote Lawrence Hayward in his song 'The Osmonds' a few years ago. 'In the Seventies there were chopper bikes/Oxford Bags and Kung-Fu fights/and men looked like Jesus in crushed velvet flares.' All of that is undeniably accurate - and I should know because, like Lawrence (and Max Boyce), I was there too. But, was any of it a good thing?

'1984 was just like 1974,' the songwriter and social commentator Jerry Dammers once noted. 'A miners strike and a load of crap in the charts.' This oddest of nostalgia trips has been building for quite a while and, to be honest, it rather baffles this blogger. It's a little bit like the annoyingly cosy nostalgia that many of my parents generation had (and, indeed, still have) for the 1930s and the 1940s. Why would anybody want to remember fondly an era of warfare and carnage, depression, deprivation, rationing and rickets? It's the same with the 1970s, frankly. Why would anyone in their right mind wish to celebrate The Era That Taste Forgot? 'In the Seventies there was long hair/there were left-over hippies everywhere/and I should know cos I was there,' wrote Lawrence Hayward in his song 'The Osmonds' a few years ago. 'In the Seventies there were chopper bikes/Oxford Bags and Kung-Fu fights/and men looked like Jesus in crushed velvet flares.' All of that is undeniably accurate - and I should know because, like Lawrence (and Max Boyce), I was there too. But, was any of it a good thing?

To this blogger, all the rose-tinted charm and whimsy for a time not that long passed is getting just a touch too far removed from the reality of the era to be entirely healthy. Just that bit too ridiculous and, frankly, goddman silly. Because for most real people, the 1970s were one of the worst times to be alive, like, ever. At least, if you were a peasant in the Middle Ages, you had a massive plague come along every few years and - if you were lucky - put you out of your misery after a few days of coughing up blood. The 1970s, were a cold time - both metaphorically and, indeed, literally. Getting all hot and sweaty under the collar to the kinky gyrations of yer actual Pan's People on Top of the Pops would only last for a few minutes each Thursday night and, after that, it was back to huddling around the gas fire with your family for a smidgen of warmth. And that was in the middle July. Even with the mass introduction of central heating when millions of council homes were 'modernised' during the early part of the decade, there remained a distinct chill about life in the era. A chill which was perfectly reflected in that infamous Ready Brek®™ advert of children going off to school on cold, dark, wet mornings with a radiation-style glow around them. As ever in the advertising world, that was an example of somewhat crass hyperbole, but something of the sort would have come in handy during the winters (particularly those of 1970, 1974, 1978 and 1979) when the snow was usually two foot high right across the country for six week and just about every school in the land was closed because the boilers couldn't cope. Classic British workmanship, you see. But still, according to the unions at least, better than any of that cheap foreign muck.

The 1970s, were a cold time - both metaphorically and, indeed, literally. Getting all hot and sweaty under the collar to the kinky gyrations of yer actual Pan's People on Top of the Pops would only last for a few minutes each Thursday night and, after that, it was back to huddling around the gas fire with your family for a smidgen of warmth. And that was in the middle July. Even with the mass introduction of central heating when millions of council homes were 'modernised' during the early part of the decade, there remained a distinct chill about life in the era. A chill which was perfectly reflected in that infamous Ready Brek®™ advert of children going off to school on cold, dark, wet mornings with a radiation-style glow around them. As ever in the advertising world, that was an example of somewhat crass hyperbole, but something of the sort would have come in handy during the winters (particularly those of 1970, 1974, 1978 and 1979) when the snow was usually two foot high right across the country for six week and just about every school in the land was closed because the boilers couldn't cope. Classic British workmanship, you see. But still, according to the unions at least, better than any of that cheap foreign muck.

To take a momentary detour since we're talking about the subject - and it's pure dead funny as a bonus - let's stick with the advertising of the decade: Advertising (particularly television advertising) in the 1970s was just about all lies. Spectacularly well told and brazen lies, let it be said - the sort of thing that's you've almost got to stand up and applaud at its sheer cheek. Such a statement is possibly true of the mass advertising campaigns of most eras, to be fair, but it was particularly applicable to the decade of Pifco, Moulinex and Ronco and their nasty 'sell it, and then stick it in the cupboard and forget it' brand of mostly-bloody-useless household labour-saving devices that your mum didn't need. Of Victor Kiam who was so impressed he bought the company. And of K-Tel and Pickwick and their thoroughly wretched and irksome TV-advertised LPs for 'people who couldn't afford proper records.'

Such a statement is possibly true of the mass advertising campaigns of most eras, to be fair, but it was particularly applicable to the decade of Pifco, Moulinex and Ronco and their nasty 'sell it, and then stick it in the cupboard and forget it' brand of mostly-bloody-useless household labour-saving devices that your mum didn't need. Of Victor Kiam who was so impressed he bought the company. And of K-Tel and Pickwick and their thoroughly wretched and irksome TV-advertised LPs for 'people who couldn't afford proper records.'  The advertising men must have been laughing their collective bell-end off at the lot of us over some of the odious, cheap, nasty, never-as-advertised plastic-fantastic tat which we all bought from them in the names of progress and modernity and so that we could say in polite company 'we've got one of them'. Laughing just about as hard as the robots did on the 'For Mash get S.M.A.S.H' adverts, in fact. They be telling us we can all do the, if you will, shake-and-vac and, as it were, put the freshness back, next, mark my words. Bastards!

The advertising men must have been laughing their collective bell-end off at the lot of us over some of the odious, cheap, nasty, never-as-advertised plastic-fantastic tat which we all bought from them in the names of progress and modernity and so that we could say in polite company 'we've got one of them'. Laughing just about as hard as the robots did on the 'For Mash get S.M.A.S.H' adverts, in fact. They be telling us we can all do the, if you will, shake-and-vac and, as it were, put the freshness back, next, mark my words. Bastards!

Anyway, moving back to the decade in general. 'In 1974, it seemed like life was in black and white,' noted The Clash's Joe Strummer, with his usual poetic turn of phrase in Don Letts' 1999 documentary on the band, Westway To The World. 'Everywhere was boarded up, it was a wasteland.' Strummer was mainly talking about the decrepit state of Britain's housing at this time, a situation which ultimately gave rise to widespread squatting - particularly in London - and, out of which the punk movement sprang virtually fully formed. But he could, just as easily, have been referring to the vast musical and cultural wilderness of the period, or to a social study of the early 1970s political landscape: 'The three day week, the blackouts, the Grunwick strike and pickets. Pretty heavy socio-politically active times,' Strummer told Uncut in 2002. 'When you see a film like Rude Boy, the beginning of that, it looks like it's a hundred years ago.' But, of course, it wasn't - many of the people reading this blog, for instance, will have lived through at least a part of the decade.

'Everywhere was boarded up, it was a wasteland.' Strummer was mainly talking about the decrepit state of Britain's housing at this time, a situation which ultimately gave rise to widespread squatting - particularly in London - and, out of which the punk movement sprang virtually fully formed. But he could, just as easily, have been referring to the vast musical and cultural wilderness of the period, or to a social study of the early 1970s political landscape: 'The three day week, the blackouts, the Grunwick strike and pickets. Pretty heavy socio-politically active times,' Strummer told Uncut in 2002. 'When you see a film like Rude Boy, the beginning of that, it looks like it's a hundred years ago.' But, of course, it wasn't - many of the people reading this blog, for instance, will have lived through at least a part of the decade.

Put simply, in the mid-1970s life was - mostly - bloody grim. Nobody had any money - apart from fictional playboy crime-fighters like Jason King and Lord Brett Sinclair - because Labour were in power and, as a consequence, everyone was either unemployed, laid-off or on strike. Or, because it was a time of equal opportunities incompetence, for the three years when Teddy Teeth was running the show from the deck of Morning Cloud, everybody was ... still either unemployed, laid-off or on strike. Or else, they were busy solving crime. Relatively competently, like Jason and Lord Brett and Jack and George from The Sweeney but, mostly, with staggering ineptitude, some sickening corruption and more than a little prejudicial racism (especially when it came to anyone Irish) in the case of The Met or The West Midlands Serious Crime Squad. And, sometimes involving manic and distressing displays of Clockwork Orange-style ultaviolence to the point of the death of a suspect in custody in the cases of the SPG with Blair Peach or the six coppers who (allegedly) brayed Liddle Towers to 'justifiable homicide' in Gateshead nick in 1976. Thus, the only other people who had any money were satin-pants-wearing pop stars with glitter on their faces and a few of the more well-paid footballers - and, most of them (the ones that weren't living as tax exiles in France, that is) were usually to be found down Georgie Best's nightclub pissing away their win bonuses and their royalty statements on champagne, blow and big dirty women.

Relatively competently, like Jason and Lord Brett and Jack and George from The Sweeney but, mostly, with staggering ineptitude, some sickening corruption and more than a little prejudicial racism (especially when it came to anyone Irish) in the case of The Met or The West Midlands Serious Crime Squad. And, sometimes involving manic and distressing displays of Clockwork Orange-style ultaviolence to the point of the death of a suspect in custody in the cases of the SPG with Blair Peach or the six coppers who (allegedly) brayed Liddle Towers to 'justifiable homicide' in Gateshead nick in 1976. Thus, the only other people who had any money were satin-pants-wearing pop stars with glitter on their faces and a few of the more well-paid footballers - and, most of them (the ones that weren't living as tax exiles in France, that is) were usually to be found down Georgie Best's nightclub pissing away their win bonuses and their royalty statements on champagne, blow and big dirty women.  Or, in the case of my locals heroes, like Supermac, Jinky Jim Smith and Hallelujah, John Tudor, oot on the pop on Gateshead High Street. And, even if, by some miracle, you were the one person in your street who did have a job (perhaps in a floor-sweeping capacity at one of the three factories in the country which were still open), inflation was rising at upwards of thirty per cent at one point in 1974. Meaning that by the time you'd walked from your house to the corner shop to buy a pint of milk, the price has risen by fourpence. And, given the state of refrigeration when the power unions were taking industrial action, by the time you got home (in the pitch black) the milk had, likely, gone off. Sourness - something there was a lot of in the 1970s.

Or, in the case of my locals heroes, like Supermac, Jinky Jim Smith and Hallelujah, John Tudor, oot on the pop on Gateshead High Street. And, even if, by some miracle, you were the one person in your street who did have a job (perhaps in a floor-sweeping capacity at one of the three factories in the country which were still open), inflation was rising at upwards of thirty per cent at one point in 1974. Meaning that by the time you'd walked from your house to the corner shop to buy a pint of milk, the price has risen by fourpence. And, given the state of refrigeration when the power unions were taking industrial action, by the time you got home (in the pitch black) the milk had, likely, gone off. Sourness - something there was a lot of in the 1970s.

As far as the class struggle went, King Crimson's Robert Fripp made an interesting point when he was interviewed by Vic Garbarini in 1981. British musicians, by and large, appeared to Fripp to be more politically aware than their American counterparts because British society's class system was then - and, possibly, still is now - so rigid and ingrained in everyone that one almost feels obliged to comment upon it. And, as a consequence, to define ones position within it. America, by contrast, was then, and remains, essentially a commercial culture and, therefore, a great deal of social mobility can tend to result. In other words, Britain had a class-conscious system in which everyone but pariahs like nouveau riche vulgarians knew their place. Escaping this sort of pigeonholing - for the working classes at least - was usually an option only available to those who have as James Bolam's character, Terry Collier, memorably noted in Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais' movie adaptation of The Likely Lads (1976), 'cracked it through football or rock and roll.' Or, as his mate Bob Ferris aptly proved, by starting to worm ones way up the greasy status pole towards middle-class respectability on the Elm Lodge Housing Estate.

And, as a consequence, to define ones position within it. America, by contrast, was then, and remains, essentially a commercial culture and, therefore, a great deal of social mobility can tend to result. In other words, Britain had a class-conscious system in which everyone but pariahs like nouveau riche vulgarians knew their place. Escaping this sort of pigeonholing - for the working classes at least - was usually an option only available to those who have as James Bolam's character, Terry Collier, memorably noted in Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais' movie adaptation of The Likely Lads (1976), 'cracked it through football or rock and roll.' Or, as his mate Bob Ferris aptly proved, by starting to worm ones way up the greasy status pole towards middle-class respectability on the Elm Lodge Housing Estate.

The 1960s were long gone, and with them, much of the radical agenda which had helped to shape those times had cracked and dissipated in a maelstrom of fractured sub-movements, confused manifestos and - not unconnected with all of this - a surfeit of promiscuity and mind-bending drugs. For the lucky. Most of us had to do with a bit of slap and tickle round the back of the bike sheds with Dirty Gillian from Mindrum Terrace and the nearest we got to getting high was the buzz you got after drinking half a bottle of Tizer a bit sharpish. The previous decade had seen British society, theoretically at least, breaking out of a straightjacket of dullness and conformity which had restrained it since Victorian times. Though it would be wrong to over-exaggerate the changes to everyday life (the fashionable clothes worn on Carnaby Street, the trendy dinner parties of Knightsbridge, South Kensington and the suburbs and the saucy goings on at The Ad Lib Club had very little to do with the lives of an average working family living on a council estate in Newcastle on a weekly wage of twenty five notes) it was, nevertheless, a time of new ideas. The era saw a proliferation of foreign restaurants opening around the country (particularly Chinese, Indian and Italian), a new hedonism in the popular cultures of music, television, film, literature and the theatre, all aided by a relaxation in the late 60s Britain's draconian obscenity laws and an increase in participation in sporting activity which saw the building of many new leisure centres.

Most of us had to do with a bit of slap and tickle round the back of the bike sheds with Dirty Gillian from Mindrum Terrace and the nearest we got to getting high was the buzz you got after drinking half a bottle of Tizer a bit sharpish. The previous decade had seen British society, theoretically at least, breaking out of a straightjacket of dullness and conformity which had restrained it since Victorian times. Though it would be wrong to over-exaggerate the changes to everyday life (the fashionable clothes worn on Carnaby Street, the trendy dinner parties of Knightsbridge, South Kensington and the suburbs and the saucy goings on at The Ad Lib Club had very little to do with the lives of an average working family living on a council estate in Newcastle on a weekly wage of twenty five notes) it was, nevertheless, a time of new ideas. The era saw a proliferation of foreign restaurants opening around the country (particularly Chinese, Indian and Italian), a new hedonism in the popular cultures of music, television, film, literature and the theatre, all aided by a relaxation in the late 60s Britain's draconian obscenity laws and an increase in participation in sporting activity which saw the building of many new leisure centres.

All of these changes happened during a decade of relative affluence and the first stirrings of genuine social mobility. The development of comprehensive education had meant that for the first time young working-class men and women were leaving school and, instead of going into traditional blue-collar occupations, were finding employment in the better paid white-collar sector. Which, usually, meant that they had more disposable income than their parents and were happy to spend it on a glut of new consumers goods - record players, radios, colour television sets, washing machines. It was also a time when attendance at football matches and other sporting events, cinemas and pop music concerts was at an all time high. This was all the upside of what the 1960s had achieved. But, with the dawn of the 1970s, the negative aspects of this embryonic new society structure, still struggling to properly define itself, were becoming apparent. The 'white-hot technology' of Harold Wilson's 1964 government hadn't produced the expected second industrial revolution. Instead, Britain's industrial base was winding down with an alarming speed. Many traditional industries were wholly failing to adapt to a changing world and the workers within them (particularly in areas like heavy engineering, mining and steel production) didn't seem to realise that by their intransigence and bolshy attitude, they were providing their enemies with enough rope to hang them. The poor, in Britain, were still poor and (when they weren't on strike) worked hard for very little reward whether they were employed in a nationalised industry or in the bowels of the capitalist system. 'Meet the new boss, same as the old boss,' according to one of the prophets of the new age, Pete Townshend.

The 'white-hot technology' of Harold Wilson's 1964 government hadn't produced the expected second industrial revolution. Instead, Britain's industrial base was winding down with an alarming speed. Many traditional industries were wholly failing to adapt to a changing world and the workers within them (particularly in areas like heavy engineering, mining and steel production) didn't seem to realise that by their intransigence and bolshy attitude, they were providing their enemies with enough rope to hang them. The poor, in Britain, were still poor and (when they weren't on strike) worked hard for very little reward whether they were employed in a nationalised industry or in the bowels of the capitalist system. 'Meet the new boss, same as the old boss,' according to one of the prophets of the new age, Pete Townshend.

There were people with agendas in all walks of life and many of these were either confused or downright sinister. The Angry Brigade - a classic example of what happens when public schoolgirls get radicalised by thinking too much - taking their lead from the Brigates Rosse in Italy and the Red Army Faction in West Germany had tried to petrolbomb their way to an anarchist utopia by burning a few clothes shops. Perhaps inevitably, it didn't happen. Feminism, the one great popular social movement of the 1960s which had actually achieved a modicum of social change, still managed to bring out all of the worst instincts and prejudices on both sides of the gender lines. When Stokely Carmichael (1941-1998), the Black Panther's president, visited the UK in 1969, he was asked by a feminist journalist what place he saw for women in his vision of harmonious multiracial future society. 'On your back, baby,' was his infamously glib reply.

Feminism, the one great popular social movement of the 1960s which had actually achieved a modicum of social change, still managed to bring out all of the worst instincts and prejudices on both sides of the gender lines. When Stokely Carmichael (1941-1998), the Black Panther's president, visited the UK in 1969, he was asked by a feminist journalist what place he saw for women in his vision of harmonious multiracial future society. 'On your back, baby,' was his infamously glib reply.  The radical left were so torn by infighting and dogmatic rhetoric that they couldn't even organise a halfway decent piss up in a brewery let alone organise themselves to fight their real enemies. So hopelessly concerned with right-on ideology were many of these groups that the vicious Monty Python’s Life of Brian parody of them ('Splitters!') is, actually, far too truthful - and, as a result, painful - to be as funny as it should be.

The radical left were so torn by infighting and dogmatic rhetoric that they couldn't even organise a halfway decent piss up in a brewery let alone organise themselves to fight their real enemies. So hopelessly concerned with right-on ideology were many of these groups that the vicious Monty Python’s Life of Brian parody of them ('Splitters!') is, actually, far too truthful - and, as a result, painful - to be as funny as it should be.

The world was changing, and no one was going to be immune from this inevitable process: On 17 October 1973, in response to the escalating Yom Kippur war, OPEC, the Arab oil producing countries, summarily cut production and quadrupled the world price of oil. This, effectively, ended the relative affluence upon which, as Ian MacDonald would subsequently write in Revolution in the Head, 'the preceding ten years of happy-go-lucky excess in the West had chiefly depended.' It's a rather less sentimental suggestion for 'the day that the Sixties (conceptually) ended' than some highly symbolic musical event like The Rolling Stones' disastrous concert at Altamont (1969), the break-up of The Beatles (1970) or the death of Jimi Hendrix (also 1970) perhaps, but, it's probably a much more realistic one.

The resulting financial crisis in Europe sent inflation spiralling and led to all sorts of ramifications in unexpected places (not least, the virtual destruction of the British film industry for the next decade and a vinyl crisis when meant the record industry almost went the same way). It was the single, chilling, moment when the Swingin' Sixties turned, almost overnight, into the 'Sober-and-Soon-to-be-Unemployed Seventies.' As a bizarre coincidence, on the very same day - 17 October 1973 - England’s football team, needing a mere victory to progress, drew 1-1 with Poland in a World Cup qualifier. This failure to reach the final stages of a tournament that England had actually won eight years previously may seem insignificant to some. But, just as that famous 'some people are on the pitch...' victory in 1966 appeared to encapsulate the spirit of an entire era - when England (and, specifically, London) was, quite literally, on top of the world - so the gloom which settled over the country during the winter of 1973-74, with its three-day weeks, powercuts, 'Cod War' with Iceland and general austerity amidst runaway inflation, conflict, national strife and whispers of an alleged right-wing military coup in the offing, was inextricably tied to the failing fortunes of Sir Alf Ramsey’s ageing side. So, you see, it was all Norman Hunter and Peter Shilton's fault.

As a bizarre coincidence, on the very same day - 17 October 1973 - England’s football team, needing a mere victory to progress, drew 1-1 with Poland in a World Cup qualifier. This failure to reach the final stages of a tournament that England had actually won eight years previously may seem insignificant to some. But, just as that famous 'some people are on the pitch...' victory in 1966 appeared to encapsulate the spirit of an entire era - when England (and, specifically, London) was, quite literally, on top of the world - so the gloom which settled over the country during the winter of 1973-74, with its three-day weeks, powercuts, 'Cod War' with Iceland and general austerity amidst runaway inflation, conflict, national strife and whispers of an alleged right-wing military coup in the offing, was inextricably tied to the failing fortunes of Sir Alf Ramsey’s ageing side. So, you see, it was all Norman Hunter and Peter Shilton's fault.

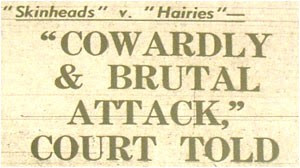

In such circumstances, many people tend to put their faith in anyone who offers easy solutions to society's problems. ‘Vote for me, and I’ll set you free,’ as The Temptations had noted in 'Ball Of Confusion' at the dawn of the decade. History, specifically the dreadful spectre of 1930s fascism in Germany, reminds us of this time after time. It should, therefore, be of little surprise that in this confused political climate, the right-wing repatriationist party, The National Front, enjoyed a spectacular rise in popularity in Britain. Formed in 1966, through a fusion of various existing far-right groups, in May 1977 the party polled over one hundred thousand votes in London’s local council elections. A series of National Front marches in the late 1970s, often through multiracial areas of London like Lewisham, Southall and Lambeth, produced numerous angry confrontations with leftist and anti-fascist groups like The Anti-Nazi League and the SWP. For the first time since the Thirties, Britain had political riots taking place on its streets.

History, specifically the dreadful spectre of 1930s fascism in Germany, reminds us of this time after time. It should, therefore, be of little surprise that in this confused political climate, the right-wing repatriationist party, The National Front, enjoyed a spectacular rise in popularity in Britain. Formed in 1966, through a fusion of various existing far-right groups, in May 1977 the party polled over one hundred thousand votes in London’s local council elections. A series of National Front marches in the late 1970s, often through multiracial areas of London like Lewisham, Southall and Lambeth, produced numerous angry confrontations with leftist and anti-fascist groups like The Anti-Nazi League and the SWP. For the first time since the Thirties, Britain had political riots taking place on its streets.

'In Great Britain there is too little discussion of racial matters,' wrote the American sociologist Thomas Cottle in 1978. 'To listen to some people is to believe there are no racial problems in the United Kingdom.' One of the great ironies, and a very revealing one, about British society during the 1970s was that whilst the subject of class was now being openly spoken about when it was, in reality, no longer the supreme overriding factor of social inequality, the well-ingrained reticence that once enveloped discussions on class, had switched to topic of race. The concept is, perhaps, an ambiguous one to grasp for readers in the genuinely more multiracial society of Britain in the Twenty First Century, but this ignores the street-level attitudes of three decades ago.

One of the great ironies, and a very revealing one, about British society during the 1970s was that whilst the subject of class was now being openly spoken about when it was, in reality, no longer the supreme overriding factor of social inequality, the well-ingrained reticence that once enveloped discussions on class, had switched to topic of race. The concept is, perhaps, an ambiguous one to grasp for readers in the genuinely more multiracial society of Britain in the Twenty First Century, but this ignores the street-level attitudes of three decades ago.  Those Britons of West Indian, African and Asian ancestry clearly, and very rightly, felt that racist attitudes in white society had, by the late 1970s, spread far beyond the small minority of bigots who advocated violent confrontation with immigrant communities. Much of the National Front's support came from decaying urban areas where there were large immigrant populations, suggesting that tolerance and fairness was in somewhat short supply. In 1976, Mark Bonham-Carter, Chairman of the Community Relations Commission, warned that Britain's black population, forty per cent of whom had been born in Britain, would not settle for second-class citizenship 'in exchange for higher living standards and the prospect of some employment. They are British, and they take the phrase "equality of opportunity" for what it means.'

Those Britons of West Indian, African and Asian ancestry clearly, and very rightly, felt that racist attitudes in white society had, by the late 1970s, spread far beyond the small minority of bigots who advocated violent confrontation with immigrant communities. Much of the National Front's support came from decaying urban areas where there were large immigrant populations, suggesting that tolerance and fairness was in somewhat short supply. In 1976, Mark Bonham-Carter, Chairman of the Community Relations Commission, warned that Britain's black population, forty per cent of whom had been born in Britain, would not settle for second-class citizenship 'in exchange for higher living standards and the prospect of some employment. They are British, and they take the phrase "equality of opportunity" for what it means.'

There was a distinctive - and quite unattractive - 'smell' about the 1970s. A smell which was somehow different from that of the world both before and after the decade. Sarah Turner's 1994 Midnight Underground short Sheller Shares Her Secret (an amusing morality tale about a girl who finds the perfect way to get even with a father who is an overbearing disciplinarian) captures, in words and images, this olfactory world of sweaty gangs of kids in bri-nylon shirts, linoleum and nylon carpets, sticky plastic furniture, stewed cabbage, over-heated gas fires, old-lady-houses full of dust and decay, dogs with bad breath and piss-stained lavatories. A smell of cheap staleness. A smell of poverty. Of rottenness. An interesting musical equivalent can be found in the often quite unnerving sounds of the ambient trance duo Boards of Canada. These musical dreamscapes have a cold, metallic surface which one critic observed 'reflect the rhapsodic and the eerie all tangled together' into a vaguely sinister paving over of Memory Lane. Their CD Music Has the Right to Children (1998) has a genuine otherworldly quality and it is possible to experience something perilously close to an out-of-body experience whilst listening to parts of it - momentarily carried away by an involuntary flood of mental images: out-of-focus rocket-scape concrete walkways and electricity pylons; tower blocks and graffiti-covered shopping centres; allotments shrouded in the early morning mist; stark images of domestic tension underscored by the sonorous hum of the television set from Play for Today or Doctor Who or The Changes. A sort of grandiose mysticism of mundanity. It is a world of wind-blown streets and abandoned crisp packets looking for somewhere to rest; a world of bus-stations full of lost luggage and lost souls. A world of crushed and broken dreams.

A smell of cheap staleness. A smell of poverty. Of rottenness. An interesting musical equivalent can be found in the often quite unnerving sounds of the ambient trance duo Boards of Canada. These musical dreamscapes have a cold, metallic surface which one critic observed 'reflect the rhapsodic and the eerie all tangled together' into a vaguely sinister paving over of Memory Lane. Their CD Music Has the Right to Children (1998) has a genuine otherworldly quality and it is possible to experience something perilously close to an out-of-body experience whilst listening to parts of it - momentarily carried away by an involuntary flood of mental images: out-of-focus rocket-scape concrete walkways and electricity pylons; tower blocks and graffiti-covered shopping centres; allotments shrouded in the early morning mist; stark images of domestic tension underscored by the sonorous hum of the television set from Play for Today or Doctor Who or The Changes. A sort of grandiose mysticism of mundanity. It is a world of wind-blown streets and abandoned crisp packets looking for somewhere to rest; a world of bus-stations full of lost luggage and lost souls. A world of crushed and broken dreams.

The Seventies, in short, were not cool, whatever anyone may say to the contrary. Not even close. Some of the music might have been, admittedly. It depended on how much money your family had to spend on luxury items like vinyl records. If you didn't live in a town then your access to the latest Jethro Tull triple-LP (or the latest Chicory Tip forty-five, for that matter) was likely to be rather limited. If you had a big brother who'd now left school, got himself a job and was happy to buy an LP every couple of weeks rather than go out of lash with his mates on a Friday night (like a couple of my friends did) then there were the joys of David Bowie, The Stooges, The Edgar Broughton Band, Lindisfarne, Mott The Hoople, The Faces, Atomic Rooster, Hawkwind, Free, Kraftwerk, Can and Bob Marley & The Wailers to discover. Which was a fairly undramatic leap from T-Rex, Slade or The Sweet but an Eval Kineval-style one from The Partridge Family and Lieutenant Pigeon. But - and this is something those who get all warm and fuzzy about what a great time, musically, the early-to-mid 1970s were should remember - for every The Who or The Rolling Stones there were many, many, many dreadful, tuneless Deep Purples, Yeses and ELPs. Even the arrival of punk didn't change everything for the better overnight. For every Clash or Jam or Buzzcocks there were charts full to the brim with Manhatten Transfer, The Doolies and Liquid Gold. And for every David Bowie there were half-a-dozen pale and piss-poor imitators.

If you had a big brother who'd now left school, got himself a job and was happy to buy an LP every couple of weeks rather than go out of lash with his mates on a Friday night (like a couple of my friends did) then there were the joys of David Bowie, The Stooges, The Edgar Broughton Band, Lindisfarne, Mott The Hoople, The Faces, Atomic Rooster, Hawkwind, Free, Kraftwerk, Can and Bob Marley & The Wailers to discover. Which was a fairly undramatic leap from T-Rex, Slade or The Sweet but an Eval Kineval-style one from The Partridge Family and Lieutenant Pigeon. But - and this is something those who get all warm and fuzzy about what a great time, musically, the early-to-mid 1970s were should remember - for every The Who or The Rolling Stones there were many, many, many dreadful, tuneless Deep Purples, Yeses and ELPs. Even the arrival of punk didn't change everything for the better overnight. For every Clash or Jam or Buzzcocks there were charts full to the brim with Manhatten Transfer, The Doolies and Liquid Gold. And for every David Bowie there were half-a-dozen pale and piss-poor imitators.  But, the good stuff WAS good, that should be noted. For a certain age group, particularly in England, it was the songs of anger, frustration and rebellion of the 1977 to 1982 period that were the soundtrack of our greasy fish-and-chip-fingered youth. Floating out from transistor radios and cheap record players, accompanied by memories of our first experiences of drink and sex and ... well, life really. Those of us from the estate of broken glass and broken dreams for whom something like The Clash's 'Stay Free' or The Jam's 'Saturday's Kids' or The Undertones' 'Teenage Kicks' - chronicled, with almost obsessive detail, our teenage lives. What we did, where we went, how we felt.

But, the good stuff WAS good, that should be noted. For a certain age group, particularly in England, it was the songs of anger, frustration and rebellion of the 1977 to 1982 period that were the soundtrack of our greasy fish-and-chip-fingered youth. Floating out from transistor radios and cheap record players, accompanied by memories of our first experiences of drink and sex and ... well, life really. Those of us from the estate of broken glass and broken dreams for whom something like The Clash's 'Stay Free' or The Jam's 'Saturday's Kids' or The Undertones' 'Teenage Kicks' - chronicled, with almost obsessive detail, our teenage lives. What we did, where we went, how we felt.

Some of the telly programmes were pretty decent – when you could watch them between all the powercuts, that is. Although again, and as with most aspects of life, a cosy nostalgia has now settled over the Seventies to such an extent that we've all conveniently forgotten the rubbish – the three thousand nine hundred and seventy five bloody episodes of Crossroads, all of the hideously stereotypical ITV sitcoms like Queenie's Castle, Love Thy Neighbour and Mind Your Language, all of the dreadful filler shows in the afternoon - Crown Court for God's sake! - all of the wretched game shows presented by Jimmy Tarbuck in his nasty golfing sweater. We've forgotten the smug arrogance of Robert Robinson on Ask the Family and the ill-begotten starchiness of Blue Peter at its most Home Counties-friendly. So, just remember all you nostalgia-buffs it wasn't all Doctor Who, The Morecambe & Wise Show, The Sweeney, UFO and Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads? There was plenty of crap too.

Although again, and as with most aspects of life, a cosy nostalgia has now settled over the Seventies to such an extent that we've all conveniently forgotten the rubbish – the three thousand nine hundred and seventy five bloody episodes of Crossroads, all of the hideously stereotypical ITV sitcoms like Queenie's Castle, Love Thy Neighbour and Mind Your Language, all of the dreadful filler shows in the afternoon - Crown Court for God's sake! - all of the wretched game shows presented by Jimmy Tarbuck in his nasty golfing sweater. We've forgotten the smug arrogance of Robert Robinson on Ask the Family and the ill-begotten starchiness of Blue Peter at its most Home Counties-friendly. So, just remember all you nostalgia-buffs it wasn't all Doctor Who, The Morecambe & Wise Show, The Sweeney, UFO and Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads? There was plenty of crap too.

There clearly was some good stuff going on during the decade, then. In a variety of different fields. If you looked around hard enough under the scatter cushions, down the back of fake-leather sofa and in the boxes gathering dust in the corner of the Utility Room, of course.

Odd bits and pieces here and there (like most eras, really). But, by and large, the Seventies were - for this blogger, anyway and I suspect for most people - pretty dreadful. An era of bad clothes, bad haircuts, bad food, bad skin, bad teeth, bad health, bad air, bad education, bad politics, bad housing, bad cars, bad sounds, bad sights, bad attitudes bad ideas and very bad solutions.

Sounds like the sort of place that nobody in their right mind would want to visit, let alone actually live in, right? A bit like Grimsby, if you like. Yeah, actually, come to think of it, that's a perfect description of the 1970s. A bit like Grimsby. Nevertheless if, even after all the above evidence has been presented, you're still feeling vaguely warm and nostalgic and are ready to slip on your stax-heal platform wedgers and massive dan-dares, finish off your cheese fondue, drink your Harvey's Bristol Cream, watch an episode of The Generation Game and then go get 'with it' down at The Purple Pussycat discotheque with all your mates – then here's a (somewhat stereotypical) checklist of twenty five vital components for your forthcoming Tom and Barbara-style self-sufficient life in the horror that was the Seventies. Remember, you have been warned.

Nevertheless if, even after all the above evidence has been presented, you're still feeling vaguely warm and nostalgic and are ready to slip on your stax-heal platform wedgers and massive dan-dares, finish off your cheese fondue, drink your Harvey's Bristol Cream, watch an episode of The Generation Game and then go get 'with it' down at The Purple Pussycat discotheque with all your mates – then here's a (somewhat stereotypical) checklist of twenty five vital components for your forthcoming Tom and Barbara-style self-sufficient life in the horror that was the Seventies. Remember, you have been warned.

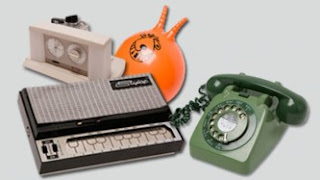

1. Keracolor Spherical TVs:

The gloriousness of the Keracolor Sphere from an era when somebody thought it was a cool idea to make a TV set that looked like a spaceman's helmet. Because, remember, this was a moment in time when the world was transfixed by the prospect of where we would be going next - to the moon and beyond. Culture, telelcommunications and technology were exploding into uncharted areas - according to the Sunday Times Colour Supplement. That supposed (imagined) space-age look had its roots in a mid-50s trend called Mid-Century Modern design probably best epitomised by the work of Charles Eames and his peers and continued through the Sixties as NASA were actually getting their shit together. In 1968 a British designer, Arthur Bracegirdle, devised and put into production the worlds first perfectly spherical TV made from Fibreglass. They loomed large in the early Seventies, with a wide range of models available - many in garish burnt orange - including floor-standing and hanging-from-the-ceiling-by-a-chain TVs, wood-effect models, even a large one with a built-in eight-track cassette player. The TVs stayed in production until the company closed down in 1977. All the pop-stars had one. But, because the cheapest colour model in 1976 cost three hundred and seventy five notes, not that many normal people did. Still, we could aspire to having one, could we not? The Seventies were, if nothing else, a decade of avarice. Something which, by the end of the 1970s, at least one politician was using as a vote winner. Greed.

That supposed (imagined) space-age look had its roots in a mid-50s trend called Mid-Century Modern design probably best epitomised by the work of Charles Eames and his peers and continued through the Sixties as NASA were actually getting their shit together. In 1968 a British designer, Arthur Bracegirdle, devised and put into production the worlds first perfectly spherical TV made from Fibreglass. They loomed large in the early Seventies, with a wide range of models available - many in garish burnt orange - including floor-standing and hanging-from-the-ceiling-by-a-chain TVs, wood-effect models, even a large one with a built-in eight-track cassette player. The TVs stayed in production until the company closed down in 1977. All the pop-stars had one. But, because the cheapest colour model in 1976 cost three hundred and seventy five notes, not that many normal people did. Still, we could aspire to having one, could we not? The Seventies were, if nothing else, a decade of avarice. Something which, by the end of the 1970s, at least one politician was using as a vote winner. Greed.

2. The Hillman Imp:

That compact little rear-engined saloon, manufactured under the Hillman marque by the Rootes Group (later Chrysler-Europe) from 1963 to 1976. An estate version - known as the Hillman Husky - was produced from 1967. Everybody's dad had one of these. Sod your Ford Cortinas and your Mini Coopers flying around Turin stealing gold, this was the car of choice for every chap with a pipe. Alternatively, if your dad was employed in something other than a floor-sweeping capacity, the Dolomite Sprint was a decent substitute. That was always supposing the odd one managed to get produced between strikes at Leyland.

An estate version - known as the Hillman Husky - was produced from 1967. Everybody's dad had one of these. Sod your Ford Cortinas and your Mini Coopers flying around Turin stealing gold, this was the car of choice for every chap with a pipe. Alternatively, if your dad was employed in something other than a floor-sweeping capacity, the Dolomite Sprint was a decent substitute. That was always supposing the odd one managed to get produced between strikes at Leyland.

3. Nylon Parkas:

The green (and, later, blue) nylon snorkel parka with the fake-fur trimming on the hood - as opposed to the earlier cotton fishtail parka popular with Mods and, therefore, cool as Frostie the Snowman's bits - attained its popular high point in Britain the 1970s. Its (very) cheap and hard wearing properties made it the jacket of choice for trampy school kids from Cornwall to Grampian. It became so popular that in many schools almost every boy - and more than a handful of the girls - had one. Check out, for example, footage of Ronnie Radford's goal for Hereford against Newcastle in the FA Cup in 1972. There's more parkas on the pitch than people. Whilst the original American N3B military parka lining was unquilted and the same colour as the outer shell, the school-type parkas usually has quilted orange lining. The measure of a school parka quickly became how grubby the orange lining got through natural wear without washing. Many schoolboy parkas ended their days with the lining that was closer to black than orange. Also, of course, the natural combination of nylon and teenage boys with rampaging hormones usually meant that the wearer quickly stank of BO worse than the local disgusting, shit-stained Harry Ramp. Brands such as Lord Anthony, Campri and Keynote made their names selling snorkel parkas though, in the 1980s the coat became associated with trainspotters and science fiction nerds, helping to create the UK term 'anorak' for such people. As such it was highly unfashionable and for a long time wearers became the subject of ridicule. Some people actually consider this development to have occurred about a decade too late.

There's more parkas on the pitch than people. Whilst the original American N3B military parka lining was unquilted and the same colour as the outer shell, the school-type parkas usually has quilted orange lining. The measure of a school parka quickly became how grubby the orange lining got through natural wear without washing. Many schoolboy parkas ended their days with the lining that was closer to black than orange. Also, of course, the natural combination of nylon and teenage boys with rampaging hormones usually meant that the wearer quickly stank of BO worse than the local disgusting, shit-stained Harry Ramp. Brands such as Lord Anthony, Campri and Keynote made their names selling snorkel parkas though, in the 1980s the coat became associated with trainspotters and science fiction nerds, helping to create the UK term 'anorak' for such people. As such it was highly unfashionable and for a long time wearers became the subject of ridicule. Some people actually consider this development to have occurred about a decade too late.

4. Hai-Karate Aftershave and Talc:

The 1970s was, of course, the era for thoroughly minging aftershave. And, as a consequence, the era for the hideously over-the-top aftershave television advert as well. Remember that stunning bird (was it Caroline Munro or is that my memory playing tricks on me?) coming out of the surf to 'Carmina Burana' to sell bottles of Old Spice? Henry Cooper and Kevin Keegan splashin' it on all over for the disgusting Brut Thirty Three? A woman's hand seductively snaking its way up a chaps chest while the guitars got louder in an advert for Denim (for Men)? Or, what about Pagan Man (by Jōvan) "taking his woman to his hut at the edge of the village for his nightly feast"? But, none of these pongy scents and cheap slogans could ever compare, in the slightest, to Valerie Leon catching one whiff of the weedy fellah wearing Hai-Karate Aftershave and Talc and turning into a feral sex-crazed tigress.

A woman's hand seductively snaking its way up a chaps chest while the guitars got louder in an advert for Denim (for Men)? Or, what about Pagan Man (by Jōvan) "taking his woman to his hut at the edge of the village for his nightly feast"? But, none of these pongy scents and cheap slogans could ever compare, in the slightest, to Valerie Leon catching one whiff of the weedy fellah wearing Hai-Karate Aftershave and Talc and turning into a feral sex-crazed tigress.  Whilst the undisputed King of the Seventies voice-over, William Franklin, solemnly informed viewers 'Be careful how you use it.' As a unique marketing ploy, in the early days each bottle of Hai Karate came with a small self-defence instruction booklet, to help wearers defend themselves against such women. Ironically, the stuff itself stank even worse than the smell of those kids who wore their parka for too long. Funny that.

Whilst the undisputed King of the Seventies voice-over, William Franklin, solemnly informed viewers 'Be careful how you use it.' As a unique marketing ploy, in the early days each bottle of Hai Karate came with a small self-defence instruction booklet, to help wearers defend themselves against such women. Ironically, the stuff itself stank even worse than the smell of those kids who wore their parka for too long. Funny that.

5. Lava Lamps:

A novelty item used entirely for decoration rather than illumination - the slow chaotic and seemingly random rise and fall of liquidic blobs of wax is suggestive of lava, hence the name. Singapore-born Edward Craven Walker invented the lamp in the 1960s. Walker's company, Crestworth, named the lamp "Astro" and also produced variations such as the Astro Mini which they presented at a Brussels trade show in 1965. Entrepreneur Adolph Wertheimer noticed it and, with his business partner William Rubinstein, bought the American rights and produced it as the Lava Lite via the Lava Corporation®™. The lava lamp became an icon of the 1960s in both Britain and America: The changing, brightly coloured displays (often in lurid greens, oranges and purples) was compared to the psychedelic hallucinations of recreational drugs, particularly LSD and no hippie commune or, indeed, fashionable middle-class dinner party, was complete without switching-on, tuning-in and, erm, dropping-off. Recently, an episode of the American TV show MythBusters demonstrated that heating a lava lamp on a stove could make it explode, and that injuries from an explosion could be fatal. So, it's probably best not to heat one on a stove, then. The inspiration for that experiment apparently came from a story concerning a man who in 2004 died after a lamp he was heating to avoid waiting for the wax to warm up exploded, sending glass into his chest and earning him a Darwin award in the process.

The lava lamp became an icon of the 1960s in both Britain and America: The changing, brightly coloured displays (often in lurid greens, oranges and purples) was compared to the psychedelic hallucinations of recreational drugs, particularly LSD and no hippie commune or, indeed, fashionable middle-class dinner party, was complete without switching-on, tuning-in and, erm, dropping-off. Recently, an episode of the American TV show MythBusters demonstrated that heating a lava lamp on a stove could make it explode, and that injuries from an explosion could be fatal. So, it's probably best not to heat one on a stove, then. The inspiration for that experiment apparently came from a story concerning a man who in 2004 died after a lamp he was heating to avoid waiting for the wax to warm up exploded, sending glass into his chest and earning him a Darwin award in the process.

6. Dad's New Sanyo Stereo Music Centre:

It's Christmas 1975 and your dad has just bought himself a new, top of the range, Sanyo Stereo Music Centre because six weeks of accumulated strike-pay had just arrived from the union. This is great, of course, since it means you can put your old Dansette, that you've had since your brother bought it in 1961, into the loft and forget about it. Along with all of the records that your brother left when he got married. Except for Charlie Drake's 'My Boomerang Won't Come Back', cos you still quite like that one. The only problem with this course of events is that your dad will not let you play any of your records on his Sanyo Stereo Music Centre. Because it is his. He bought it to play his records. This, despite the fact that your dad, in fact, has only three records - Lonnie Donegan's Greatest Hits (Pye), The World of Val Doonican (Decca) and, the soundtrack to South Pacific which he's had since 1956 and which is, now, scratched to buggery.

Along with all of the records that your brother left when he got married. Except for Charlie Drake's 'My Boomerang Won't Come Back', cos you still quite like that one. The only problem with this course of events is that your dad will not let you play any of your records on his Sanyo Stereo Music Centre. Because it is his. He bought it to play his records. This, despite the fact that your dad, in fact, has only three records - Lonnie Donegan's Greatest Hits (Pye), The World of Val Doonican (Decca) and, the soundtrack to South Pacific which he's had since 1956 and which is, now, scratched to buggery.  Mind you, the bonus of this is that you now get to call the Dansette that you've had since 1961 your own. Which is a double-edged sword, however, as it means that any scratches the rusted stylus makes on your new Paul McCartney and Wings single will be down to your equipment and replacing it will be your responsibility. And, it's at this point in your life, shortly after your twelfth birthday, that you realise what a total bloody gyp the whole 'won't it be great when I'm grown up and I can do whatever the hell I like?' -thing is.

Mind you, the bonus of this is that you now get to call the Dansette that you've had since 1961 your own. Which is a double-edged sword, however, as it means that any scratches the rusted stylus makes on your new Paul McCartney and Wings single will be down to your equipment and replacing it will be your responsibility. And, it's at this point in your life, shortly after your twelfth birthday, that you realise what a total bloody gyp the whole 'won't it be great when I'm grown up and I can do whatever the hell I like?' -thing is.

7. Disgusting Wallpaper:

Let's face it, the 1970s was a decade when the colour orange wasn't just fashionable, it was downright de rigeur. Everything about home decoration in the era was garish - over-bright, sunburst hues and odd, "don't touch that"-type textures. This was the era of Flocks, Embossed, Vinyl Covered, Anaglypta, Woodchip and Fabrics. Of horrible, ghastly modernist print patterns of flowers and art-deco designs that made the interior of your gaff look like something from the more disturbing corners of a damaged brain. It was, as noted earlier, the era that style - and taste and elegance - waved a little white flag and forgot about. And what was hanging in your living room was a daily reminder of that fact.

Everything about home decoration in the era was garish - over-bright, sunburst hues and odd, "don't touch that"-type textures. This was the era of Flocks, Embossed, Vinyl Covered, Anaglypta, Woodchip and Fabrics. Of horrible, ghastly modernist print patterns of flowers and art-deco designs that made the interior of your gaff look like something from the more disturbing corners of a damaged brain. It was, as noted earlier, the era that style - and taste and elegance - waved a little white flag and forgot about. And what was hanging in your living room was a daily reminder of that fact.

8. The Green Lady by Vladimir Tretchikoff:

She looks, unsmiling, down and to her left a slightly haughty and dismissive gesture suggesting that she is, frankly, rather pissed off to be hanging on your wall. Dressed in an exotic gold-collared robe, her hands are folded out of sight. So far, so unremarkable, except for her skin, a strange blue-green. In the 1960s and 70s, Chinese Girl - to give the 1950 portrait its proper title - graced many a living room wall across the globe. It became one of the world's most popular paintings when made into art prints. The model was, apparently, the daughter of a restaurant owner whom the Russian-born artist Vladimir Tretchikoff (1913-2006) met in San Francisco. The painting was, actually, Tretchikoff's second variation on the theme, after the first (using a different model) was destroyed in a robbery at the artist's studio in South Africa. If you didn't have a copy of this on you front room wall in the 1970s then, chances are, you had a poster featuring Albert Korda's image of Che Guevara (if you were a Communist). Or, three china ducks like Hilda Ogden.

So far, so unremarkable, except for her skin, a strange blue-green. In the 1960s and 70s, Chinese Girl - to give the 1950 portrait its proper title - graced many a living room wall across the globe. It became one of the world's most popular paintings when made into art prints. The model was, apparently, the daughter of a restaurant owner whom the Russian-born artist Vladimir Tretchikoff (1913-2006) met in San Francisco. The painting was, actually, Tretchikoff's second variation on the theme, after the first (using a different model) was destroyed in a robbery at the artist's studio in South Africa. If you didn't have a copy of this on you front room wall in the 1970s then, chances are, you had a poster featuring Albert Korda's image of Che Guevara (if you were a Communist). Or, three china ducks like Hilda Ogden.

9. Fish Fingers and/or Spaghetti Hoops For Tea:

Bird's Eye and Heinz - the two companies more responsible than any other for the diet of the Seventies. I suppose you could add Golden Wonder and Cadburys and Findus in there if you were looking to complete the set. But, essentially, it was these guys who created the template for what was going to be in the stomach of the nation on an average night. Add in a healthy couple of slices of Mother's Pride and a thick covering of Lurpak (and, if you were really lucky, some of King Edward's finest fried in the best of what Mr Atora had to offer) for yer tea and you were ready to face the ordeal of getting your homework done before Nationwide started.

But, essentially, it was these guys who created the template for what was going to be in the stomach of the nation on an average night. Add in a healthy couple of slices of Mother's Pride and a thick covering of Lurpak (and, if you were really lucky, some of King Edward's finest fried in the best of what Mr Atora had to offer) for yer tea and you were ready to face the ordeal of getting your homework done before Nationwide started.

10. Clackers:

The toy to have circa Christmas 1972, Clackers were, basically, two solid plastic marbles, each about two inches in diameter, attached to a ring with piece of string. The "aim" of the game - such as it was - was to strike them together making a hugely annoying racket. The player put his or her finger in the ring, allowing the marbles or balls to hang below. Through a gentle up-and-down hand motion, the two balls swing apart and together, making the clacking noise that give the toy its name. After a little practice, it was possible to get the marbles swinging so that they knock together above the hand as well as below. Some people got very good at it. But, inevitably, some children got injured whilst playing with them: Besides being fairly heavy and fast-moving, the marbles were made of hard acrylic plastic that could, if given enough force, shatter upon striking each other, presenting a safety hazard. Kids loved them but doctors and teachers weren't so impressed following a frightening succession of Clacker accidents. After a national outbreak of badly bruised arms they were pretty much withdrawn from sale. There is a recurring urban legend that the clacker spheres were made of glass, although no one has ever produced an actual glass set. The confusion may have arisen because many sets were made of transparent coloured acrylic. The toys enjoyed a brief renewal of popularity in the 1990s. But them ones weren't like they were in t'maaaa day.

After a little practice, it was possible to get the marbles swinging so that they knock together above the hand as well as below. Some people got very good at it. But, inevitably, some children got injured whilst playing with them: Besides being fairly heavy and fast-moving, the marbles were made of hard acrylic plastic that could, if given enough force, shatter upon striking each other, presenting a safety hazard. Kids loved them but doctors and teachers weren't so impressed following a frightening succession of Clacker accidents. After a national outbreak of badly bruised arms they were pretty much withdrawn from sale. There is a recurring urban legend that the clacker spheres were made of glass, although no one has ever produced an actual glass set. The confusion may have arisen because many sets were made of transparent coloured acrylic. The toys enjoyed a brief renewal of popularity in the 1990s. But them ones weren't like they were in t'maaaa day.

11. Kipper ties:

Fashion designer Michael Fish created the kipper tie in 1966 working out of his establishment in Piccadilly. The primary characteristics of the kipper tie were its extreme breadth and often garish colours and patterns - particularly when worn in a combination with a genuine 1971-style shirt from John Collier ('the window to watch!') with a collar so wide that it covered four counties. It has been proposed that the name "kipper tie" is a reference to the extreme breadth of the tie resembling a kipper or, as a sly reference to the designer's last name.

The primary characteristics of the kipper tie were its extreme breadth and often garish colours and patterns - particularly when worn in a combination with a genuine 1971-style shirt from John Collier ('the window to watch!') with a collar so wide that it covered four counties. It has been proposed that the name "kipper tie" is a reference to the extreme breadth of the tie resembling a kipper or, as a sly reference to the designer's last name.

12. The Chopper:

No, not Ron Chopper Harris (he was a different sort of Seventies icon) but, rather, the definitive statement in personalised transport for the upwardly mobile nine year old, circa 1973. The Raleigh Chopper was, without doubt, the single coolest bike ever made ... even if it was just about impossible to ride for more than ten yards without falling off and grazing your knees. Styled after the dragster, with a long seat and larger back wheels, it was the first designer bicycle for kids. And, possibly, the most unstable too. A triumph of style over practicality, it first went on sale in 1970 - covered in knobs, whistles and horns that didn't really do anything (except the gear lever that made you fall off when changing gear). Despite its total impracticality you felt like A Biking God when you had one and, by 1973, it had become the country’s best selling bike.

even if it was just about impossible to ride for more than ten yards without falling off and grazing your knees. Styled after the dragster, with a long seat and larger back wheels, it was the first designer bicycle for kids. And, possibly, the most unstable too. A triumph of style over practicality, it first went on sale in 1970 - covered in knobs, whistles and horns that didn't really do anything (except the gear lever that made you fall off when changing gear). Despite its total impracticality you felt like A Biking God when you had one and, by 1973, it had become the country’s best selling bike.

13. A Top-Loader VCR:

A previously discussed, home video recorders had been around in various forms since the 1960s, if you happened to have more money than the average gross national product of a small third world country. By the mid-1970s, however, technology had moved on. Now, for just four hundred quid or so, you could buy - for example - a Philips N1500 (marketed in 1972) the first, genuine, domestic home VCR. So at least, you know, people with jobs like Record Producer could afford one. Big chunky top-loaders - the size of a large suitcase - that took big chunky tapes (the size of a big chunky hardback book and which, themselves, cost about forty quid a pop ... for sixty minutes worth of tape!) the N1500 was the must-have new toy for the one kid in your school whose dad worked in more than a floor-sweeping capacity. You know, the one who also had a Dolomite Sprint and who took his family on holiday to Spain instead of Butlin's at Filey. Thus, many would be the day when fifteen or more children would pour into this family's living room for the novelty of watching, again, last week's episode of Doctor Who ... only to find that his mum had taped The Brothers over it on Sunday night. Which, of course, ensured that the video-kid got a damned good kicking. And, rightly so in my opinion. You don't build up expectations like that only to crush them underfoot. There was enough of that going on elsewhere in the Seventies.

By the mid-1970s, however, technology had moved on. Now, for just four hundred quid or so, you could buy - for example - a Philips N1500 (marketed in 1972) the first, genuine, domestic home VCR. So at least, you know, people with jobs like Record Producer could afford one. Big chunky top-loaders - the size of a large suitcase - that took big chunky tapes (the size of a big chunky hardback book and which, themselves, cost about forty quid a pop ... for sixty minutes worth of tape!) the N1500 was the must-have new toy for the one kid in your school whose dad worked in more than a floor-sweeping capacity. You know, the one who also had a Dolomite Sprint and who took his family on holiday to Spain instead of Butlin's at Filey. Thus, many would be the day when fifteen or more children would pour into this family's living room for the novelty of watching, again, last week's episode of Doctor Who ... only to find that his mum had taped The Brothers over it on Sunday night. Which, of course, ensured that the video-kid got a damned good kicking. And, rightly so in my opinion. You don't build up expectations like that only to crush them underfoot. There was enough of that going on elsewhere in the Seventies.

14. Watneys Party Seven:

Hosting a 1970s house party, for real authenticity you needed somebody to bring along a Watneys Party Seven or it's smaller brother, the Watneys Party Four. Quite simply, no party of the era was complete without one. Lager hadn't really come on the scene yet and it was keg bitters like Watneys Red Barrel, Double Diamond and Worthington 'E' which were normally the drink of choice. Even though they all tasted like stewed piss. The Party Seven was first made available in 1968 - as a promotion Watneys sold a Sparklets Beertap with a free voucher for a can of Party Seven for 59s 9d. Watneys Party Seven initially sold for fifteen shillings (that's 75p to you and me). Thankfully Harp, Skol and Carling were just a few years away.

Quite simply, no party of the era was complete without one. Lager hadn't really come on the scene yet and it was keg bitters like Watneys Red Barrel, Double Diamond and Worthington 'E' which were normally the drink of choice. Even though they all tasted like stewed piss. The Party Seven was first made available in 1968 - as a promotion Watneys sold a Sparklets Beertap with a free voucher for a can of Party Seven for 59s 9d. Watneys Party Seven initially sold for fifteen shillings (that's 75p to you and me). Thankfully Harp, Skol and Carling were just a few years away.

15. Miniskirts or Hot Pants:

I didn't have a sister but lots of my mates did. So, the big question whenever I visited any of their houses around 1972 or 73 was "what's the best thing she can be wearing that will enable me to see her panties - a miniskirt or hot pants?" Contrary to common belief, the miniskirt didn't suddenly disappear in 1969 as every woman in the land came under the influence of Germaine Greer. If you ever get the chance to have a look at a mid-Seventies episode of Top of the Pops you'll still see plenty of them around and still giving good wiggle. But, Hot Pants, there were - very definitely - a fashion that had a brief, and huge, flowering around 1972 (having found great popularity years earlier among European prostitutes apparently). Incidentally, the answer to the question - in the case of Mark Blackett's sister, Jill anyway - was the miniskirt. Definitely.

16. Star Jumpers:

A V-necked sweater in one colour (often brown or black but, occasionally blue or white) with three stars knitted in the centre in a different colour. All the Northern Soul kids with their massive flares used to wear them down the youth club thinking there were as cool as milk. And, briefly, around 1975, it was something that pretty much all the kids wanted. To have on when you were riding your chopper bike and wearing big cheap shades that made you look like Elton John. But, actually, Star Jumpers were rather trampy and after a while, they even found their way into an infamous football chant in which one team's fans would taunt the opposition for one of their number having "a three-star jumper halfway up his back." Unlike most of the things on this list, finding a photo example of one proved to be really difficult. Doesn't nobody still have a star jumper in their attic?

And, briefly, around 1975, it was something that pretty much all the kids wanted. To have on when you were riding your chopper bike and wearing big cheap shades that made you look like Elton John. But, actually, Star Jumpers were rather trampy and after a while, they even found their way into an infamous football chant in which one team's fans would taunt the opposition for one of their number having "a three-star jumper halfway up his back." Unlike most of the things on this list, finding a photo example of one proved to be really difficult. Doesn't nobody still have a star jumper in their attic?

17. The Spacehopper:

The Spacehopper was - as I'm sure everyone remembers (because, let's face it, just about everybody in Britain had one) - a heavy rubber balloon about sixty to seventy centimetre in diameter, with two rubber handles protruding from the top. A valve at the top allowed the balloon to be inflated by a bicycle pump then a child would sit on top, holding the two handles, and bounce up and down on it. In practical terms, this was a very inefficient form of locomotion but its simplicity, ease of use, low cost and cheerful appearance appealed to children. Until they burst it after four or five tries - which is what happened to mine. And, unlike a bicycle tyre, you couldn't really fix it with a puncture repair kit. The Spacehopper was said to have been invented by Aquilino Cosani of Ledragomma, an Italian company that manufactured toy rubber balls. He patented the idea in Italy in 1968. Spacehoppers were introduced to the UK in 1969 when the Cambridge Evening News contained an advertisement for the hopper in November of that year and described it as a "trend". Although in practical terms they served absolutely no useful purpose whatsoever, nevertheless they became a major craze. Caused a hell of a lot of skinned thighs and strained ankles as well as I remember. Under no circumstances should they have been used whilst wearing shorts, swimming trucks or just your underwear as the bouncing motion gave yer knackers a good clout every now and then so you really needed some padding.

Until they burst it after four or five tries - which is what happened to mine. And, unlike a bicycle tyre, you couldn't really fix it with a puncture repair kit. The Spacehopper was said to have been invented by Aquilino Cosani of Ledragomma, an Italian company that manufactured toy rubber balls. He patented the idea in Italy in 1968. Spacehoppers were introduced to the UK in 1969 when the Cambridge Evening News contained an advertisement for the hopper in November of that year and described it as a "trend". Although in practical terms they served absolutely no useful purpose whatsoever, nevertheless they became a major craze. Caused a hell of a lot of skinned thighs and strained ankles as well as I remember. Under no circumstances should they have been used whilst wearing shorts, swimming trucks or just your underwear as the bouncing motion gave yer knackers a good clout every now and then so you really needed some padding.

18. Ice Lollies with Space-Age Names:

There were two great producers on ice lollies in the UK in the 60s and 70s - Walls and Lyon's Maid.

In keeping with the space race the Russians and Americans were having at the time, these two seemed hell-bent on producing the most spectacular and outrageous heaven on a stick imaginable. This was the era of Zoom, Blast, Mivi, Luv and, best of all, the legendary Fab. Launched in 1967 and, supposedly, designed primarily for the three million girls in Britain aged five to fifteen, the Fab was based around Gerry Anderson's Thunderbirds TV series. Priced at six (old) pence it consisted of strawberry fruit ice and vanilla ice cream with top dipped in chocolate and coated with 'hundreds and thousands' sugar confectionery. Needless to say, all the lads quickly discovered them and any idea that it was a girly lolly went right out of the window. The description on the packaging read "Real Strawberry and vanilla flavour ice lolly with chocolate flavour coating (five per cent) and sugar strands (five per cent)." Ah, them were the days.

In keeping with the space race the Russians and Americans were having at the time, these two seemed hell-bent on producing the most spectacular and outrageous heaven on a stick imaginable. This was the era of Zoom, Blast, Mivi, Luv and, best of all, the legendary Fab. Launched in 1967 and, supposedly, designed primarily for the three million girls in Britain aged five to fifteen, the Fab was based around Gerry Anderson's Thunderbirds TV series. Priced at six (old) pence it consisted of strawberry fruit ice and vanilla ice cream with top dipped in chocolate and coated with 'hundreds and thousands' sugar confectionery. Needless to say, all the lads quickly discovered them and any idea that it was a girly lolly went right out of the window. The description on the packaging read "Real Strawberry and vanilla flavour ice lolly with chocolate flavour coating (five per cent) and sugar strands (five per cent)." Ah, them were the days.

19. Beans Bags:

If your parents were particularly mad pretentious middle-class wankers with absolutely no frigging common sense whatsoever then you might have some of that 'living plastic furniture' which killed people in that Doctor Who episode with the Autons in your front room. But, if not, then you made do with lounging around on a bean bags which were cool at first but, once you'd been sitting on them for a couple of hours, really hurt your arse. Another trouble was, after a while, they absolutely minged but were impossible for your mum to wash. So, most of them ended up in the garden shed. Next to your burst Spacehopper.

But, if not, then you made do with lounging around on a bean bags which were cool at first but, once you'd been sitting on them for a couple of hours, really hurt your arse. Another trouble was, after a while, they absolutely minged but were impossible for your mum to wash. So, most of them ended up in the garden shed. Next to your burst Spacehopper.